The Disciplinary Panel’s full written reasons from this case are set out below. A penalties hearing is being held at 10am on Monday 12 October to consider and set out penalties. Written reasons for penalties will then follow in due course.

- On 1 July 2015, the Disciplinary Panel of the British Horseracing Authority (BHA) began the hearing of an enquiry into allegations of corruption against five individuals that concerned seven races in which AD VITAM (IRE) participated between November 2011 and March 2012. The races in question are identified in the Notes to these Reasons. The hearing lasted six days, following which the Panel considered its decision which is now set out below.

The Charges

- David Greenwood, a professional gambler and the owner of AD VITAM (IRE) between March 2011 and at least June 2012, was alleged to be the principal mover in a conspiracy with the other four to run the horse other than on its merits for lay betting purposes, contrary to Rule (A)41. He was also said to have given improper riding instructions – i.e. instructions which could or would prevent the horse from achieving its best possible placing – to Michael Stainton and Claire Murray, the jockeys, in the first six of the races, in breach of Rule (B)58.2. Thirdly, he was alleged to be in breach of Rule (A)36, which outlaws the giving of inside information to others for reward. Finally, he was said to be in breach of Rule (A)50.2 in that he did not supply his telephone billing records to the BHA and did not agree to attend an interview by BHA investigators looking into this and other matters.

- Stainton was said to have conspired, contrary to Rule (A)41, with Mr Greenwood to ride the horse otherwise than on its merits in races 1, 4, 5 and 6, and actually to have done so in races 1 and 5. In respect of races 1 and 5, he was therefore also alleged to be in breach of Rule (B) 58.1.

- Murray faced similar charges. She was alleged to have conspired with Mr Greenwood to ride AD VITAM (IRE) otherwise than on its merits in races 2 and 3, and actually to have done so in those races. Again, she was alleged to be in breach of Rule (B)58.1 in respect of those rides.

- Kevin Ackerman was the fourth alleged conspirator. He was said to have acted in breach of Rule (A)41 by obtaining and using inside information from Mr Greenwood about AD VITAM (IRE) when placing the lay bets against that horse in some of the races. He faced a second allegation of breach of Rule (A)37 – that he provided reward to Mr Greenwood for inside information supplied to him.

- Finally, Kenneth Mackay was said to have been another conspirator, in breach of Rule (A)41, who obtained and used inside information from Mr Greenwood about AD VITAM (IRE) when placing the lay bets against that horse. Like Mr Ackerman, he was also alleged to be in breach of Rule (A)37 by providing reward to Mr Greenwood for the inside information supplied to him.

Representation

- The BHA’s case was presented by Louis Weston. Mr Greenwood and Mr Ackerman were both represented by Ian Winter QC, instructed by Stewart Moore Solicitors. The two jockeys, Stainton and Murray, were assisted by Paul Struthers of the Professional Jockeys Association (PJA). Though Mr Struthers is not a lawyer, the Panel gave permission for him to act on their behalf. The Panel was grateful for the help he gave and the thoughtfulness and expertise he brought to his task.

Abuse of process application

- The first day of the hearing of the enquiry was occupied by the consideration of an application made by Mr Winter QC. He argued that the evidence to be relied upon by the BHA from Sophie Griffiths in particular and from her husband, the trainer David Griffiths, was so tainted and untrustworthy that it was not necessary to hear them to decide upon its reliability. Further, he contended that failures by the BHA to give disclosure of documentation compounded the problem and made a fair hearing impossible. In support of the first contention, he argued that the BHA had had no concerns with the questioned races until well over a year after they took place, and that the central plank of the case was an alleged confession by Murray to Mrs Griffiths before race 3 at Wolverhampton on 18 November 2011 to the effect that she was going to ride to lose the race on the instructions of Mr Greenwood. He relied upon the late emergence of this allegation together with what he said were other indications that Mrs Griffiths’s evidence was unreliable – in particular that she was the source of assertions about the true ownership of a number of horses which the BHA had either abandoned (in the case of Kate Walton) shortly before an enquiry, or had found to be too unreliable to support any case against Mr Greenwood. Mr Winter QC reinforced these observations by contending that the BHA ought to disclose all relevant material about how their investigation in this case developed.

- The Panel dismissed the application. The threshold to be met when seeking to stop a hearing as an abuse of process is a high one – is the hearing incapable of being conducted fairly? None of the points argued by Mr Winter QC, taken individually or cumulatively, established that proposition. All the matters which he raised about the conduct of the BHA investigation and about the credibility of the evidence of Mrs Griffiths and Griffiths were capable of being explored by him in cross-examination. The BHA’s case that the betting of Mr Ackerman and Mr Mackay was in some way informed by knowledge of what was to happen in the questioned races was not so unreliable on its face as to justify a refusal to investigate it further. Mr Winter QC’s complaint about disclosure from the BHA was based on his submission that the materials he sought were relevant. That was not the correct test. The BHA’s obligation was to disclose material which (i) they positively relied upon and which (ii) might harm their case. That obligation had been recognised in correspondence before the enquiry began. It was the basis upon which the Chairman of this Panel proceeded when considering disclosure applications before the enquiry began. There was no ground for suspecting that the obligation had not been met before or after the enquiry began. The giving of disclosure in accordance with that obligation had been supervised by Mr Weston, the independent counsel who presented the BHA’s case.

- Accordingly, the Panel decided to hear the case and the evidence to be put forward by both sides.

David Greenwood, AD VITAM (IRE) and the early races

- Mr Greenwood told the Panel he was a professional gambler. After university, he said he began a graduate placement with William Hill in about 2002, doing various jobs with them until late 2004, including with William Hill radio. In 2005 he did some TV work for Sky and then worked with Timeform radio, but after that concentrated on gambling, principally on horse racing. He said that his profit since 2005 was just over £5 million, and that in 2010 he had won £865,000 and not far short of that in 2011. He estimated his betting turnover per week at about £1 million, with the aim of making a small percentage of that turnover. The Panel accepted that, in 2011 at least, Mr Greenwood was a high-stakes gambler who had had considerable success. That was confirmed by the evidence of others, notably Tom Chignell the BHA betting analyst.

- The Panel’s caution in accepting what should have been largely uncontroversial material from Mr Greenwood about his history arose from its general approach to his evidence. When giving his evidence, he gave a detailed account of his involvement in the racing of AD VITAM (IRE), as well as of his contacts with the horse’s trainers and jockeys and with his various friends and associates in the racing world. For a variety of reasons, the Panel felt compelled to treat his account with great caution. Thus –

- he failed, at any time before giving his evidence before the Panel, to commit himself to any detail of what he remembered of his contacts with trainers and jockeys or of his dealings with friends such as Mr Ackerman.

- As will be seen from the Panel’s conclusions about the Rule (A)50 issue, he evaded giving an account in interview with investigators and failed to produce his telephone records.

- His Schedule (A)6 form contained considerable detail of the nature of the legal arguments to be advanced, and general denials of wrongdoing, but set out next to nothing of Mr Greenwood’s own account of, for instance, what he discussed with the horse’s trainers or jockeys.

- That deficiency in Mr Greenwood’s Schedule (A)6 form was pointed out before the hearing, and a direction from the Chairman of the Panel required Mr Greenwood to produce sufficient detail of his factual case in advance of the hearing.

- His response (through his solicitor) was to repeat his earlier denials that he had given instructions to jockeys to stop AD VITAM (IRE) or had told Mr Ackerman or anyone else that this might happen. But again, nothing about what if anything he remembered he did say was disclosed.

- When he came to give evidence before the Panel, he gave for the first time some detailed evidence of his exchanges and conversations with trainers and jockeys. The Panel gained the overriding impression that this evidence was the product of his calculation of what was to his advantage rather than genuine recollection, and this was consistent with his prior failure to commit himself, whether in an interview (which he evaded), or in his Schedule (A)6 form, or in his response to the Chairman’s direction of 23 June 2015.

- These considerations persuaded the Panel that, basically, Mr Greenwood’s evidence could not be trusted unless it was corroborated by reliable evidence from others or by the Panel’s judgement of the probabilities.

- Mr Greenwood acquired AD VITAM (IRE) in March 2011. He claimed it after it won at Kempton on 10 March, and sent it to Griffiths, whom he had known from their days on William Hill radio. Initially their efforts with the horse were collaborative. It was tried over a range of trips from 8 to 11½ furlongs in its eight races up to Ripon on 4 July, and with a variety of headgear. Mr Greenwood would generally choose the jockey and either choose or have a final say about what races to enter. In six of those eight early races, it was ridden by a female apprentice, chosen (Mr Greenwood accepted) because he liked to give rides to girls, especially if pretty. Note 4, which sets out the betting relevant for this enquiry, shows that Mr Greenwood did have some sizeable win or place bets on some of these races, but these were on the two occasions it was ridden by first Michael O’Connell and then by Martin Harley. Over the course of these races, AD VITAM (IRE)’s official handicap rating dropped from 64 to 56, and it finished in a place just once at Redcar. The overall picture, though one of general lack of success, gives credence to Mr Greenwood’s evidence that AD VITAM (IRE) was meant to be a “fun horse”.

- After the Ripon race, the horse had a wind operation, though exactly what was never made clear. It returned to racing at Southwell on 30 August, when Murray rode it for the first time, finishing last and being dropped a further 4lbs to 52 in the handicap. A race at Wolverhampton on 29 September, when ridden by Julie Cumine, was followed by Stainton’s first two rides of AD VITAM (IRE): at Wolverhampton on 6 October and Brighton on 13 October. Stainton was selected for the ride by Mr Greenwood. Their relationship was much closer than the usual jockey/owner relationship and closer than Stainton was prepared to admit in interview and evidence. They had known each other well for some years by 2011. Each described the other as a “friend” and Mr Greenwood told Griffiths that Stainton was his “best friend”. On one occasion, but on an unknown date, Mr Greenwood gave a large amount of cash – perhaps £3500 to Stainton’s partner. Stainton and Mr Greenwood had from time to time gone together to assess horses for potential purchase. And Stainton was supplying information to Mr Greenwood about prospects for horses he rode. One example was LITTLE PERISHER, a horse which some people, Mrs Griffiths among them, thought Mr Greenwood owned though he later said he did not. A Facebook exchange on 15 November 2011 between Mrs Griffiths and Mr Greenwood records Mrs Griffiths asking “do u run Little Perisher on Fri as well”. Mr Greenwood answered “Stainton rode him in work last week and thinks he’s ready…”

- For the 6 October race, a weak contest over 8½ furlongs at Wolverhampton, Mr Greenwood had win and place bets totalling £4186. Stainton rode the horse prominently, lead over 2 furlongs out but eventually finished 2nd. The horse was dropped a further 2lbs in the handicap to 50. At Brighton on 13 October over 8 furlongs, Mr Greenwood’s back bets totalled £7045. Stainton again gave the horse a strong ride, up with the leaders to challenge 2 furlongs out. Though 2nd with a furlong to go, AD VITAM (IRE) was eventually beaten into 4th place. The handicapper raised the horse 2lbs to a mark of 52 for this run. The reason for noting these rides in some detail is because of the notable contrast they provide to Stainton’s rides in the races listed in Note 3. While the Panel is of course aware that a ride less strong than a jockey’s strongest effort does not automatically amount to a breach of the Rules, the contrast between the Brighton ride and the Kempton ride, to the ride in November (race 1) was so marked as to be damning.

Race 1

- By the time of the Kempton race on 2 November 2011, therefore, AD VITAM (IRE) had achieved just two placed finishes in twelve runs for Mr Greenwood, and had been raised 2lbs for its last run. Mr Greenwood had just lost his largest bet on AD VITAM (IRE) since the Redcar race in May 2011. At Kempton, AD VITAM (IRE) was drawn on the outside – what the witnesses referred to as the “coffin draw”. But there were a number of startling aspects of the ride given by Stainton. First, he missed the break entirely. The recordings show that he did not make any effort to dip down to drive his horse forward just before the gates opened, as all the other jockeys did. When the gates did open, the horse’s head was facing left. While the recordings do not make it possible to say one way or the other whether Stainton caused this, it contributed to the slow start. The Panel eventually concluded that his failures of jockeyship at the start were deliberate. Shortly after the start, AD VITAM (IRE) had lost several lengths. This was remarkable given that he had been told by Griffiths to race handy as this was a shorter than usual trip for the horse of 7 furlongs. Stainton began to push AD VITAM (IRE) forward on the outside of the field, and by the 4 furlong marker was still on the outside and just back from mid-division. The field was by this stage racing on the turn. At the 4 furlong marker, Stainton took a hold of the horse. But this was not to drop into a position nearer the rail – he remained on the outside. Further, he continued to race wide, leaving a gap of more than a horse’s width between his mount and the nearest horses to him on his inside. The Panel could find no honest explanation for racing so wide, and Stainton could not supply one. AD VITAM (IRE) had lost ground by the 3 furlong marker. In the straight, he was initially carried marginally wider by another horse, but instead of continuing with a straight run, he switched inside and began a sharply rightward angled run to the finish. He did not begin serious effort till 2 furlongs out, by which time his chance was long lost. AD VITAM (IRE) finished 6th, staying on through beaten horses, and losing by a total of 6 lengths.

- Taking this ride as a whole, therefore, the Panel concluded that it amounted to a breach of Rule (B)58 of the kind described in Rule (B)59.2 – a deliberate failure to ride the horse on its merits. There were simply too many startlingly poor features of the ride to permit a less serious conclusion. He plainly did not ride to the instructions from Griffiths. For reasons to be explained, the Panel considered that he was in fact riding to instructions from Mr Greenwood, who wanted the horse to finish down the field to try to get a more sympathetic handicap mark. Mr Greenwood did not back AD VITAM (IRE) in this race, but did back another runner on which he lost £1250 (see Note 4). The Panel did not accept his evidence that the position he took was just because of the poor outside draw for AD VITAM (IRE).

Races 2 and 3

- The next two races both featured Murray as the jockey. They were 6 furlong races at Wolverhampton on 11 and 18 November 2011. Mr Greenwood gave her the rides because Stainton was unavailable owing to a suspension for misuse of the whip. Before describing these races, it is appropriate for the Panel to set out its findings upon an important central aspect of the BHA’s case – that before the race on 18 November, Murray told Mrs Griffiths that she had orders from Mr Greenwood not to finish in the first 4. The findings on this were bound to inform the view which the Panel took of the rides.

- On 18 November, Mrs Griffiths saddled up AD VITAM (IRE) and led the horse out onto the racecourse. Her husband was not present that day. She said she asked Murray “whose instructions are you riding to today?”. According to Mrs Griffiths, Murray’s reply was that she had had different instructions, and that Mr Greenwood had told her to “jump out, stay wide and don’t finish in the first 4”. Mrs Griffiths then told her not to be so stupid and that she should ride to Griffiths’s instructions to jump out, be prominent and finish in the best place possible. Murray’s version was that she made no mention of any instructions from Mr Greenwood and that she was intending to ride to the instructions she recalled from Mrs Griffiths – “to jump out, make all and win as far as you can”.

- In seeking to resolve this conflict, Mr Winter QC and Mr Struthers urged the Panel to approach Mrs Griffiths’s evidence on the basis that it was an invention by a dishonest witness. Mr Winter QC even called another witness, the trainer David Brown, on a collateral issue designed to persuade the Panel that Mrs Griffiths could not be trusted. His evidence was said to show that Mrs Griffiths had made a false claim for personal injury damages arising out of an accident during her earlier employment by Mr Brown. But in the Panel’s view it came nowhere near establishing this. Mr Brown’s hazy recollection of what was said in a solicitor’s letter he saw just once many years before did not demonstrate that she was putting forward a false claim, and even if what he did remember of the letter was an accurate recall of it, the Panel was in no position to decide that what it said was false or that Mrs Griffiths was responsible for any false statements in it. The Panel accepted her evidence that she did not persist with the claim after starting a new chapter in her life with Griffiths.

- Nor was the Panel persuaded that Mrs Griffiths must have given false evidence to the BHA about horse ownerships. Mr Winter QC relied upon the fact that the BHA withdrew its case against Kate Walton in an earlier enquiry this year and upon the fact that the BHA did not pursue other enquiries based upon her information in this regard. The detail of Mrs Griffiths’s contributions on this topic is largely unknown, and in any event seems to have consisted of reporting what she thought or understood. Non-reliance upon this by the BHA falls miles short of showing that she was making dishonest allegations.

- So, in resolving what was said at Wolverhampton on 18 November, the Panel proceeded on the basis of its assessments of the witnesses and the probabilities emerging from other relevant evidence. Mrs Griffiths impressed the Panel as an honest witness, though combative at times. There were errors of recall in her evidence, but that did not make her a liar. Murray was a quiet person, nervous of the enquiry proceedings, but she too impressed as basically straightforward. The Panel had very much in mind the testimonial from her employer, Mr Brown, that she was a reserved person, but entirely trustworthy.

- An important part of the evidence on this issue was the record of Mrs Griffiths’s Facebook exchange with Mr Greenwood just an hour after the race, when she was preparing to return home with the horsebox. Mr Greenwood suggested this record was fabricated, but the Panel concluded it clearly was not. Mr Greenwood did not disclose his side of the record. This is the exchange:

5:12pm

Sophie Emma Griffiths

She told me on the way out ur orders she also said she had 3 different orders to ride to so she was going to stay wide fall back behind horses in the straight don’t finish in the first 4 and I was not nasty to her I told her she should have been sat more handy and it was nothing like daves orders it was an identical race to last week I know u don’t want him to win dave said that he never would without a tongue strap anyway I’m not stupid it would be nice to know what the hell your plan is for the horse hell knows what we have done wrong to you

5:25pm

David Greenwood

Sophie. I’ve spoken too Claire and according too her she said nothing of the sort too u. U really need too watch the race. Claire is flat out from the gate. The horse gave his all.”

- The Panel decided that there had been a conversation between Mrs Griffiths and Murray along the lines described in that Facebook entry, but that crucially it did not include Murray saying she was instructed not to finish in the first 4. The Facebook entry appears to be a combination of recounting a pre-race conversation and a description of how the horse ran. It is more likely that Murray said something to the effect that she was told by Mr Greenwood to stay out of the first 4 during the race – i.e. to hold the horse up. Mrs Griffiths, who was very angry about the ride afterwards and the departure from the instructions she and her husband had given, misunderstood this. The Panel was further influenced to conclude that on this occasion Mr Greenwood did not instruct the jockey to give AD VITAM (IRE) a stopping ride by these factors –

- Murray was not nearly so well known to Mr Greenwood as was Stainton. He was much too sharp to try to make a corrupt bargain with a jockey he did not know well.

- As Mr Winter QC submitted, if Murray had had such an instruction and was part of a conspiracy to stop AD VITAM (IRE), it is most improbable she would have revealed this so unguardedly to someone whom she knew full well was not part of the conspiracy.

- Mrs Griffiths did not tell anyone in authority at Wolverhampton of this conversation, though she thought she told her husband of this when she got home. He did not remember that. He was uncertain when he learned of this, but recognised that such a conversation should have been reported promptly to the BHA. Yet there was no such report to the BHA until April 2013, when it was mentioned to Mark Beecroft during a stable inspection, triggering an investigation of this line of evidence. In the Panel’s view, this delay indicates Mrs Griffiths was much less clear about what she was told at the time than she later became. She later read her Facebook exchange in a way that led her to a mistaken (but honest) view that Murray had told her of an instruction to stop the horse from Mr Greenwood.

- What of the rides in races 2 and 3? Both were remarkable spectacles. In race 2, the horse had an unfavourable draw. Murray did have instructions from Mr Greenwood to stay wide out of the kickback, off the pace, and to come through horses in the straight. By contrast, she had been told by Griffiths to jump out and race prominently. She rode a race much nearer to Mr Greenwood’s instructions. She remained almost extravagantly wide of the rest of the field after the break and before the turn for home. Coming to the straight, she did switch left and push, though weakly, into a gap between horses. AD VITAM (IRE) began to make serious progress and was moving better than any other runner when she was caught up in a complicated multi-horse event of interference. She was badly bumped a couple of times by other victims of the interference. This unbalanced her and nearly unseated her, causing her to stop riding. But for this incident, the Panel thought she would probably have won the race. In fact, she finished 4th, beaten 2 ¾ lengths by the winner.

- For race 3, the Panel again determined that she rode a race nearer to Mr Greenwood’s wish that the horse be held up, rather than complying with her instructions from Griffiths to jump out and race prominently. Again from a wide draw she kept wide initially and to the rear of the field. Though her effort in the straight did not match that of other more experienced apprentices in the race, she did use her whip four times. AD VITAM (IRE) ran on to finish 5th.

- The Panel’s overall conclusion on these two races was that she rode weakly, but that was all she was capable of, and hence she was not in breach of the Rules. She was inexperienced, and later came to recognise that she did not have the ability to ride professionally, and so she relinquished her licence.

- That leaves for consideration Mr Greenwood’s instructions to her, which she was following rather than those from Griffiths. The Panel was left in no doubt that he gave them because he thought they would contribute to a poor run down the field. And he was concerned to conceal the contents of those instructions. In the Facebook exchange with Mrs Griffiths after the 18 November race, in passages following those already quoted, he kept repeating to Mrs Griffiths that the horse was not able to run to her husband’s instructions because it had been “flat out”. Mr Greenwood (who was a stranger to false modesty) described himself to the Panel as one of the best five race readers in the country, so this description of the race, which is patently false, was his device at the time to conceal that he had given Murray different instructions. There were undoubtedly other factors which he hoped would contribute to poor results as well – a distance shorter than the horse’s best; the use of an inexperienced and weak jockey not able to give a ride of the strength to which the horse was more likely to respond; and a poor draw in both races. But as those instructions, contrary to Mr Greenwood’s expectations, did not prevent AD VITAM (IRE) from delivering a challenge in race 2 which would have won the race but for the interference, the Panel did not find him in breach of Rule (B)58.2 in relation to them. The same applies for race 3.

Races 4, 5 and 6

- After the row between Mrs Griffiths and Mr Greenwood following race 3 at Wolverhampton, which continued in the Facebook exchanges between them, part of which has been quoted above, Mr Greenwood decided to remove AD VITAM (IRE) from Griffiths’s yard. He arranged for it to go to the livery business run by Stainton’s father a few days after the race. There AD VITAM (IRE) remained until 7 January 2012, when it was returned to training with Micky Hammond. In the intervening 7 weeks, AD VITAM (IRE) appears to have been kept stabled, with minimal exercise. He had a bout of colic soon after arriving, but Stainton told the Panel it was not serious and that the horse recovered within a day or two.

- Hammond took the horse in because he had empty boxes, but had no expectation of its abilities. He believed that it had come to him direct from Griffiths, which explains why he was prepared to race it on 20 January 2012, which was in fact within the 14 day period for which a horse must be in a licensed yard before running. His misapprehension must have been caused by Mr Greenwood.

- In fact, Hammond took remarkably little interest in the horse. He left the selection of races and jockeys to Mr Greenwood. It was ridden in work by Stainton. When it arrived at the yard, Hammond had no concern about its general health but said it was carrying condition. The race at Wolverhampton on 20 January 2012 (race 4) was a poor run and the horse was never on terms. Stainton was its jockey. While there was no criticism of the ride, it showed the horse had a pronounced lack of race fitness, finishing 11th of 12. It was dropped 2lbs in the handicap to a mark of 48.

- In race 5, again at Wolverhampton on 2 February 2012 over 9 ½ furlongs, Stainton held the horse up. But just after the 3 furlong marker, when he was making some progress, he stopped riding for a few strides. He said this was because his horse was being intimidated from the outside. But the recordings show no such thing. He had ample room to continue to make a challenge. All the other riders were getting to work on their mounts at this time. Taken in isolation, one might regard this as an error of judgement. But given the wider context, the Panel decided that he was doing this as a precaution to ensure the horse ran down the field, as Mr Greenwood had required. That amounted to a breach of his obligation to ride the horse on its merits. He finished 8th of 13.

- Race 6 was again at Wolverhampton on 9 February, this time over 6 furlongs. Again, there was no criticism of the ride. The horse had a poor draw, never got on terms and remained always behind, finishing 10th of 13. This produced a further drop in the handicap to 46. In each of races 4, 5 and 6 Stainton was prepared, in the Panel’s view, to ride to lose if necessary (at Mr Greenwood’s direction), and he actually did so in race 5.

- The next race at Wolverhampton on 8 March, however, was instrumental in explaining to the Panel what the purpose of the previous six races really was. It was over 7 furlongs and AD VITAM (IRE) was off a mark of 46. It had a more favourable draw. From the outset Stainton rode with a vigour that was quite absent in races 1, 4, 5 and 6. This was the first race since Brighton in October 2011 in which Mr Greenwood backed AD VITAM (IRE). He staked a total of £15,659 in the win and place markets. Stainton raced prominently right up with the lead throughout but met with difficulty in running at the 1 furlong marker. Nevertheless he drove the horse into the lead inside the final furlong but was caught and headed at the finish by the winner, who had come late and from wider behind. Stainton’s effort on this occasion was, like in the October race at Brighton, a stark contrast with his rides in races 1, 4, 5 and 6. As Mr Greenwood’s betting shows, this was a race which he and Stainton were trying to win.

- There was no direct evidence of any reward passing from Mr Greenwood to Stainton for his conduct in these races. However, the Panel concluded that there must have been some. Whether it took the form of continuing patronage with rides, a cash payoff or some other reward (or even a combination of all three), it is not possible to say.

The lay betting – Kevin Ackerman and Kenneth Mackay

- It will be noted that the Panel has expressed its conclusions about the rides in races 1-6 and the associated conspiracy between Mr Greenwood and Stainton to ensure poor runs by AD VITAM (IRE) without reference to the lay betting by Mr Ackerman or Mr Mackay. That betting is detailed in Note 4. The reason for this is that the Panel came to the view that the activities and agreement of Mr Greenwood and Stainton were not related to this lay betting. Mr Greenwood and Stainton acted as they did to bring off back-betting coups for Mr Greenwood in the Wolverhampton race on 8 March, a scheme which was only partially successful, and in its next race, again at Wolverhampton, on 16 March, a scheme which failed. Nevertheless, the Panel also found that the lay betting by Mr Ackerman and Mr Mackay was inspired by information provided by Mr Greenwood.

- Mr Ackerman was a close friend of Mr Greenwood, who for instance often stayed at his house. They were in regular phone contact. He accepted that his bets on or against AD VITAM (IRE) at least may have been influenced by Mr Greenwood’s view of its prospects, but denied getting any information from him that made him feel he was doing anything wrong. He was rather vague in his evidence about his betting in races 1 to 6. For race 1, for instance, he could not remember why he had placed lay bets against AD VITAM (IRE) for the first time, having previously backed it on some of the occasions when Mr Greenwood did. He said that the horse’s draw might have been a big factor. He offered no real explanation for his betting in races 2 and 3. In the Panel’s view, his back bet on LITTLE PERISHER in race 3 was clearly influenced by Mr Greenwood’s information from Stainton that the horse was ready to win (see the Facebook exchange referred to earlier in these reasons at paragraph 15). This showed a degree of detail passing from Mr Greenwood to Mr Ackerman which was much greater than either was prepared to admit. For races 4, 5 and 6, his explanations were vaguer still. He said that he knew the horse by that stage and had the confidence to lay big.

- As Mr Chignell’s evidence established, these lay bets by Mr Ackerman fell outside his usual pattern. The lay bets for races 1 and 2 were his 2nd, 3rd and 9th largest lay bets of 2011, and the 2012 bets were also among his largest that year. The Panel felt bound to conclude that this level of confidence was influenced by information from Mr Greenwood that AD VITAM (IRE) was not going to perform in these races because Stainton would ride to lose if necessary. For the two Murray rides, his confidence was influenced by Mr Greenwood’s information that the horse would not win because his instructions to the jockey would help to provide a poor run. In the case of the Murray rides in races 2 and 3, however, the Panel has already found that those instructions did not include a requirement to stop the horse and were not otherwise a breach of the Rules by Mr Greenwood. So they cannot involve any breach by Mr Ackerman.

- The Panel accepted the submission of Mr Winter QC that the Ackerman bets in races 1-6 were trivial in money terms from Mr Greenwood’s perspective. That contributed to the Panel’s conclusion that there was no conspiracy between Mr Greenwood and Mr Ackerman. Mr Greenwood was far too smart to place lay bets against AD VITAM (IRE), either personally or through others, and had no real interest in what Mr Ackerman would do with the information he provided. The Panel decided that Mr Greenwood did not know what Mr Ackerman was doing with the information provided. For this reason, it acquitted both Mr Greenwood and Mr Ackerman of breaches of Rule (A)36 and Rule (A)37. The BHA’s submission that the facility of an office which Mr Ackerman arranged for Mr Greenwood at Towcester (where Mr Ackerman was the Chief Executive) was some sort of payoff for the information was rejected. That arrangement had been in place for some time before the events with which this enquiry was concerned.

- That leaves for consideration the allegation that Mr Ackerman’s betting amounted to a “corrupt practice” and therefore a breach of Rule (A)41.1. In the light of the findings of fact above, it is not necessary to go through the detailed submissions about the correct approach to the Rules following the High Court decision in McKeown v BHA in 2009, or the decisions of the BHA’s Appeal Board in Babbs and Celaschi (2013) or Knott (2015). It is enough to note simply the explanation given in Knott for the earlier decision in Babbs and Celaschi –

“the basis on which Babbs and Celaschi was decided was that the mere placing of a lay bet on the basis of Inside Information does not, without more, amount to a corrupt or fraudulent practice contrary to Rule (A)41; and that the provision of information to enable such a lay bet to be made does not, without more, put the provider of such information in breach of Rule (A)37 of assisting or encouraging or causing another person to act in contravention of the provision of that Rule. We agree with that, and we reject the BHA’s contention that the case was wrongly decided.”

- Where, as here, the information from Mr Greenwood included an indication that Stainton was prepared to ride to lose if necessary, there is present the extra ingredient which makes corrupt at least lay betting influenced by it. The Panel therefore found that Mr Ackerman’s lay betting for races 1, 4, 5 and 6 amounted to a corrupt practice contrary to Rule (A)41.1.

- Mr Mackay chose not to attend the enquiry. He therefore avoided questions about the explanation he gave to investigators in interview for his lay bets against AD VITAM (IRE) in races 1 and 2. This explanation was to the effect that he had lost a large amount of money through betting at the end of October 2011, and decided to change tactics to place large pre-race bets to try to recoup his position. Mr Mackay was a professional gambler concentrating very largely on in-running betting.

- Prior to November 2011, he had in fact placed pre-race back bets on AD VITAM (IRE) on three occasions, on each of which Mr Greenwood was also a substantial backer. His change of tactics in November 2011 consisted of three pre-race lay bets of which two were against AD VITAM (IRE) in races 1 and 2. For race 1, the liability risked through his account with Betfair and Betdaq were the 7th largest he ever took. For race 2, the liability risked was the largest he ever took. He told the investigators in interview that these positions were based upon his judgements of the horse’s form, the draw, the lack of support in the early betting market, and in the case of the second race upon the booking of Murray to ride.

- Mr Mackay admitted knowing Mr Greenwood, whom he would see at racecourses as both were in-running gamblers. He said he knew him to speak to, but had never really been involved with him. Mr Greenwood, however, disowned any real knowledge of Mr Mackay, and said he had to be shown a photograph of him to know who he was. While there was no evidence of phone contact from Mr Mackay’s phone to Mr Greenwood, the position with Mr Greenwood’s phone is unknown because he did not disclose his records. The Panel formed the view that they must have known each other to a much greater degree than either was prepared to admit, because of their frequent association at racecourses. Mr Mackay’s back betting on AD VITAM (IRE) before November 2011 on occasions when Mr Greenwood was also backing his horse was too much to be coincidence, and also showed contact between them and a flow of information from Mr Greenwood to Mr Mackay.

- The Panel decided that information from Mr Greenwood influenced Mr Mackay’s lay bets in races 1 and 2. There was no obvious reason for him to try a new approach alongside his generally profitable in-play betting, particularly when the first of his so-called change of tactics bets, against GALLANTRY on 1 November 2011, had made him a substantial loss. The relative size of his lay bets for races 1 and 2 also contradicts his untested assertion that it was based on form and other judgements of publicly available information. He was placing those bets because he knew from Mr Greenwood that Stainton was prepared to ride to lose if necessary in race 1 and that Murray had been given instructions by Mr Greenwood which it was hoped would contribute to a poor run.

- As in the case of Mr Ackerman, however, the Panel took the view that Mr Mackay was not party to any conspiracy – he was simply picking up on and using information from Mr Greenwood, in all probability without Mr Greenwood’s knowledge. But again similarly to the case of Mr Ackerman, his use of this information for race 1 was a corrupt practice and therefore a breach of Rule (A)41.1. For reasons already given, his use of the information provided for race 2 was not corrupt, because there was no breach of the rules by Murray or by Mr Greenwood in relation to his instructions for that race (more by luck than judgement in Mr Greenwood’s case). The Panel was not prepared to infer that any price was paid by Mr Mackay for this information: it was provided by Mr Greenwood to someone he evidently trusted and it was no part of Mr Greenwood’s purpose to make money from lay betting. Hence there was no breach by Mr Greenwood of Rule (A)36 or by Mr Mackay of Rule (A)37.

David Greenwood and the Rule (A)50 charge

- On 25 July 2012, John Burgess, an investigating officer with the BHA, wrote to Mr Greenwood asking him to attend an interview about a number of matters, including matters relating to AD VITAM (IRE), his association with jockeys and trainers, his own betting activity, and his association with individuals whose betting exchange accounts were under investigation. That description was sufficient to enable Mr Greenwood to understand the areas to be covered in interview. He was asked to reply by 10 August 2012 to indicate whether he would agree.

- He replied on that date, saying that he was considering his options including whether to take legal advice. Mr Burgess responded on 13 August, asking for a decision by 20 August. Again on the deadline day, Mr Greenwood wrote back asking for further detail about the nature of the investigation. That was detailed to which he was not entitled. On 28 August, Mr Burgess again responded to explain why further detail would not be provided and specifying that he should reply by 7 September to agree a date between 17 and 28 September 2012 for the interview. The response, once again sent on the deadline date of 7 September, was to the effect that the suggested dates were not convenient and that he was prepared to be interviewed in October. Mr Burgess e-mailed him on 18 September to say that he was prepared for the interview to take place on 9 October, one of the dates Mr Greenwood had suggested. On 4 October, Mr Greenwood replied to a message from Mr Burgess of the same date saying that he had not received the e-mail of 18 September, an untrue answer in the Panel’s view, and now said that the arrangement for 9 October was impossible. Mr Burgess’s response, again on 4 October, required Mr Greenwood to agree a day in either of the weeks commencing 15 or 22 October. Mr Greenwood did not respond substantively to this or a chasing message from Mr Burgess of 15 October until 25 October 2012. On this occasion he reverted to a demand for further information before agreeing to an interview. Once again, the BHA responded by letter of 16 November, on this occasion from Danielle Sharkey in the BHA’s compliance department, explaining why further information would not be provided and asking Mr Greenwood to make contact with Mr Burgess by no later than 23 November to finalise a date for an interview. She further enclosed a new request for production of telephone billings by 30 November. At this stage, Mr Greenwood resorted to the excuse of being unable to open e-mail attachments and to suggesting that the letter had gone astray. On 14 December, he professed to find this “a confusing matter” and was going to seek representation. He did not do this, on his own evidence until 9 January. On 31 January 2013, Miss Sharkey wrote to say that as he had failed to agree a time and place for interview and had failed to produce his telephone records, an application for exclusion would be made to the Disciplinary Officer. The letter contained a last gasp offer to agree to be interviewed and to provide the records by no later than 7 February 2013. On 7 February, solicitors acting for Mr Greenwood wrote professing his intention to cooperate, and saying that they hoped to be in a position to provide a substantive reply “shortly”. Nothing further was heard from Mr Greenwood or his solicitors by 19 February 2013, when he was made the subject of an exclusion order.

- That history revealed, in the Panel’s view, a clear pattern of evasion by Mr Greenwood. It showed that he failed to agree a time and a place for interview on a number of occasions. A variety of dates was specified by the BHA during the correspondence, none of which he agreed. And the history also plainly showed that he failed to produce the telephone records required of him within the time specified. Subject to one further point the breach of Rule (A)50.2 was clearly made out.

- The further point was the ingenious contention by Mr Winter QC that Mr Burgess was not an “Approved Person” for the purpose of making a request for information under Rule (A)50.1. He did not make the same argument in relation to Miss Sharkey’s request for telephone records as authorised by Ben Gunn, a Director of the BHA.

- An “Approved Person” is defined in Rule (A)48 to be a person authorised by the Authority to exercise a variety of powers including the power to request information or records. Mr Weston on behalf of the BHA was unable to produce any internal record identifying which employees of the BHA were regarded as Approved Persons. He suggested that Mr Burgess could be regarded as such because he gave evidence that he was. In the Panel’s view that did not establish his case. However, the terms of his contract of employment and the very nature of the job he was employed to do as an Investigating Officer do show that he was properly to be treated as an Approved Person. The requirement for separate and additional authorisation for information such as telephone billings that is referred to in Rule (A)50.3 and Rule (A)50.4 is a distinct process that is not required to be followed in order to require an interview.

- Hence Mr Winter QC’s point provided no defence to the charge, which the Panel found proved.

Conclusions

- Mr Greenwood and Stainton engaged in a conspiracy contrary to Rule (A)41.1 and Rule (A)41.2 to seek to ensure that AD VITAM (IRE) ran down the field in races 1, 4, 5 and 6.

- Mr Greenwood (the owner of AD VITAM (IRE)) gave instructions (contrary to Rule (B)58.2) to Stainton to ride in races 1, 4, 5 and 6 in a way which could, and in races 1 and 5 did, have the effect of preventing AD VITAM (IRE) from achieving its best possible placing.

- In races 1 and 5, Stainton rode AD VITAM (IRE) in breach of his obligation by Rule (B)58.1 to ride the horse on its merits.

- Mr Greenwood’s purpose in getting Stainton to ride in this manner was for handicapping reasons: it was done to try to reduce the horse’s Official Rating to a mark at which Mr Greenwood judged it would be more competitive.

- Neither Mr Greenwood nor Stainton acted in breach of the Rules as above for the purpose of a lay-betting conspiracy.

- Mr Greenwood was not in breach of Rule (A)36 by communicating inside information to betting exchange account holders for reward. Though he did communicate inside information to Mr Ackerman and Mr Mackay, he was unaware of its use and there was no reward involved.

- Mr Greenwood was in breach of Rule (A)50.2 between 11 July 2012 and 31 January 2013 because he failed to agree a time and a place for interview by the BHA investigating officer, because he failed to attend any such interview, and because he failed to supply his telephone billing records to the BHA as requested.

- Murray was not in breach of Rule (A)41 or Rule (B)58.1 in relation to races 2 and 3. In reaching this conclusion, the Panel did not accept the evidence of Mrs Griffiths that she was told by Murray before race 3 that she (Murray) had been instructed by Mr Greenwood to finish out of the first four in the race. However, the Panel emphasises that it concluded that Mrs Griffiths and her husband gave honest evidence to the Panel. The Panel’s eventual conclusion was that Mrs Griffiths misunderstood what was said to her about the riding instructions which Murray had been given by Mr Greenwood.

- The Panel did not find that Mr Greenwood gave Murray instructions to ride AD VITAM (IRE) otherwise than on its merits. While he expected that his instructions would contribute to a poor run, in the event they did not do so, and he was not in breach of Rule (B)58.2.

- Mr Ackerman was in breach of Rule (A)41.1, but not of Rule (A)41.2. He became aware from Mr Greenwood that AD VITAM (IRE) was likely to run down the field in races 1, 4, 5 and 6 because of the possible co-operation of Stainton in handicapping runs. He placed lay bets against AD VITAM (IRE) in those races. He was not in breach by virtue of his betting for races 2 and 3.

- Mr Ackerman was not in breach of Rule (A)37 because he was not providing reward to Mr Greenwood for the information which informed his lay betting against AD VITAM (IRE) for races 1, 4, 5 and 6, and he did not otherwise assist, encourage or cause Mr Greenwood to act in contravention of the Rules.

- Mr Mackay was in breach of Rule (A)41.1, but not of Rule (A)41.2. He became aware that AD VITAM (IRE) was likely to run down the field in race 1 because of the possible co-operation of Stainton in handicapping runs. He placed lay bets against AD VITAM (IRE) in that race. He was not in breach by virtue of his lay betting for race 2.

- Mr Mackay was not in breach of Rule (A)37 because he was not providing reward to Mr Greenwood for the information which informed his lay betting against AD VITAM (IRE) in race 1, and he did not otherwise assist, encourage or cause Mr Greenwood to act in contravention of the Rules.

Penalties

- For Stainton and Mr Greenwood the Panel started from the guidance appearing for breaches of Rule (B)58 and (A)41. The recent amendment of the Rule (A)41 guidance means that the Rule (B)58 guidance is relevant for both. This says that for cases of deliberately riding down the field for reward, or knowing it had been layed to lose, the penalty range is 5 – 25 years with an entry point of 8 years disqualification.

- The Panel did accept that their conduct in this case was materially different and less serious than a lay betting conspiracy, as it was not designed to cheat bettors with a supply of “knowing” money to match their back bets. But it did nevertheless involve cheating those who may have chosen to back AD VITAM (IRE).

- In the case of Stainton, the Panel did not accept the argument that a suspension only was appropriate, because that will ordinarily be the penalty for a “handicapping run”. That ignores the findings made by the Panel that Stainton was part of a conspiracy to do this over a number of rides, did so for two of them and must have been rewarded for this. However, the Panel did accept that he was the minor actor in this and very much under the influence of Mr Greenwood.

- Having decided therefore that the guidance and range of penalty set out at paragraph a) on page 10 was not right for this case, the Panel settled upon a disqualification of 2 years as appropriate for Stainton’s breaches.

- In Mr Greenwood’s case, it was necessary to reflect his much greater responsibility for what was done. He corrupted Stainton. He was doing this for his own hoped-for financial gain with a back betting coup. That merited, in the Panel’s view, a disqualification of 6 years.

- Mr Greenwood was also separately in breach of Rule (A)50 through his failure to attend an interview and his failure to disclose telephone records. That was entirely distinct from the breaches already considered. The Guide suggests a penalty range of 1 – 3 years disqualification for this, with an entry point of 18 months. Mr Greenwood’s breach was a considered and prolonged one here, so the Panel imposed a disqualification of 2 years, to run consecutively with the 6 years penalty, making a total of 8 years in all. It rejected the submission that the period of the disqualification should run from February 2013, when Mr Greenwood was excluded for non-production of records. That exclusion and its continuation was in a sense his choice, because he did not produce records or come for an interview. It is necessary for him and others to appreciate that interviews and records disclosure are vital parts of the regulator’s resources for policing horseracing, and that failure to co-operate will lead to heavy penalties.

- Turning to Mr Ackerman, the penalty guidance prescribed in his case was an exclusion (because he was not a registered person) of between 6 months and 10 years, with an entry point of 3 years. The Panel viewed his conduct as opportunistic, and accepted he took no part in the corrupt behaviour of Stainton and Greenwood. It was urged on his behalf that the consequences for him of an exclusion, endangering his continued employment as CEO of Towcester, should lead to a lesser penalty than exclusion. His co-operation in the investigation and the relatively small size of his lay betting were also relied upon. The Panel did not, however, feel that his status as CEO at Towcester provided any reason for a more lenient penalty. In fact, his position gave him all the more reason to behave with care and within the Rules. But a departure from the 3 years entry point certainly was called for, because his wrongdoing and that of Stainton and Mr Greenwood fell into different compartments.

- The Panel eventually decided upon an exclusion of 6 months and a fine of £5,000 for Mr Ackerman.

- The case of Mr Mackay was to be treated in much the same way as Mr Ackerman’s. His financial gains were similar, but he too was divorced from the conspiracy of Stainton and Mr Greenwood. He is however a registered owner, so in his case the penalty is a 6 month disqualification plus a fine of £5,000.

- The penalties of disqualification or exclusion (as the case may be) take place with immediate effect from the date of the penalties hearing, 12 October 2015.

Notes to Editors

1. The Panel for the hearing was: Tim Charlton QC (Chair), Edward Dorrell and Ian Stark.

2. A summary of the findings is as follows:

David M Greenwood

In breach of Rules (A)41.2, (A)41.1, (A)50.2 and (B)58.2

Not in breach of Rule (A)36

Michael Stainton

In breach of Rules (A)41.2 and (A)41.1 and (B)58.1

Claire Murray

Not in breach of Rule (A)41 or Rule (B)58.1

Kevin Ackerman

In breach of Rule (A)41.1

Not in breach of Rule (A)41.2 or (A)37

Kenneth Mackay

In breach of Rule (A)41.1

Not in breach of Rule (A)41.2 or (A)37

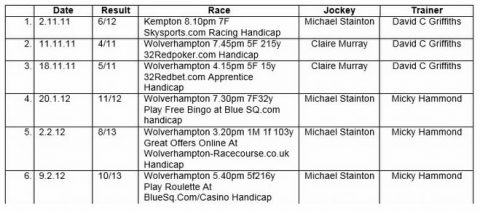

3. The table of races is as follows

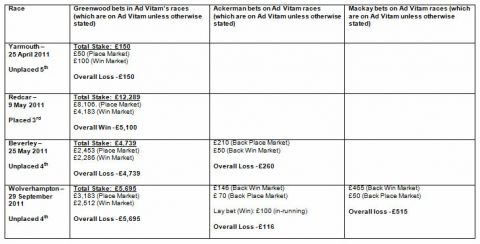

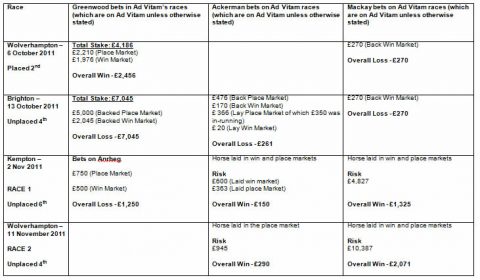

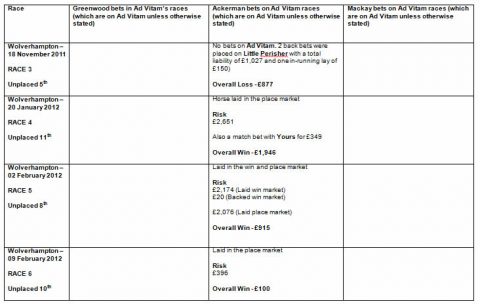

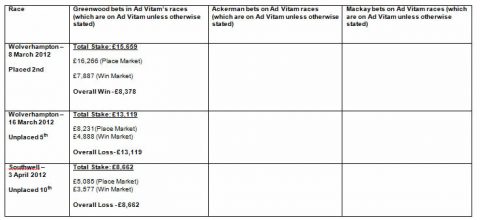

4. The betting details are as follows:

5. Details and potential penalties for the Rules where breaches have been found are as follows:

(A)41 Involvement in corrupt or fraudulent practices in relation to racing

http://rules.britishhorseracing.com/Orders-and-rules&staticID=126207&depth=3

Where the corrupt or fraudulent practice included the actual or intended breach(es) of any other Rule(s) by other individuals involved in such practice, see penalty for such Rule(s) if the corresponding penalty exceeds the entry point and range below.

Where there is no such associated Rule(s):

Entry point: Disqualify/Exclude 3 years

Range: 6 months – 10 years

(B)58 General requirement for a horse to be run on its merits and obtain best possible placing

http://rules.britishhorseracing.com//Orders-and-rules&staticID=126359&depth=3

The range applied depends on the finding by the Panel as to the circumstances, and the full table can be found on pages 10 and 11 of the Guide to Procedures and Penalties.

Deliberately not riding a horse to obtain the best possible placing for personal reward or knowing that it had been layed to lose:

Entry point: Disqualify 8 years; Horse suspended

Range 5 – 25 years

(A)50 Requirement to provide information or records

http://rules.britishhorseracing.com//Orders-and-rules&staticID=126216&depth=3

Entry point: Disqualify/Exclude 18 months

Range: 1 year – 3 years